2009

With Shoemakers of Hira Mandi

With Shoemakers of Hira Mandi

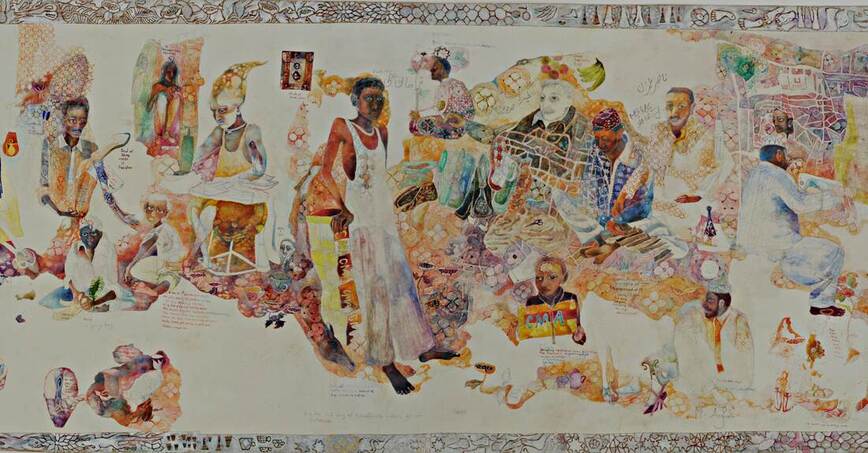

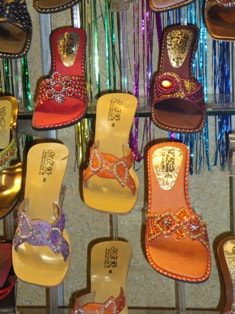

Shoemakers of Hira Mandi. Detail. Watercolour on wasli. 200cmx25cm (entire).

Making Shoemakers of Hira Mandi with the shoemakers of CMA Shoes in Old Lahore and at their village outside Lahore. Photography by the artist.

. In summer in 2009 I was in Lahore at NCA where I was trying to learn more about miniature. At NCA they have a pundit who makes their wasli paper, and I was trying out a paper that was thinner, more flexible, cheaper than the wasli used for Floating in Hindustan.

I was zealously concerned with keeping the paper clean and pristine, and had not begun making life drawings in the scrolls. So when I went walking in the Old City it was only to look really. At that time had many tiny manufacturing workshops and I wanted to learn about working conditions of people. But as I spoke very little Urdu I just walked round and round, too shy to try to engage with any workers.

I kept being drawn back to the old city. I would walk there from the college, all the way through Anarkali, fuelled by chai and street food.

The old city was a labyrinth of paths, uneven and often slippery and one day I slipped on a step and fell down into a tiny room.

The workshop was filled with men making shoes. It was summer and the room felt like a fan-forced oven. The shoemakers cheered, they took my arms, sat me down, smiled and smiled. So patient with my lack of language. They stuffed me with tea and biscuits, and I stayed and stayed. I pulled out the white paper, put it on the workshop floor and drew portraits. The men smiled and cheered me on. They loved looking at their portraits. I don't think I would have had the courage to return had they not responded to the drawing this way.

The shoemakers were men and boys. They lived, ate, slept, and worked on the workshop floor six days a week. On the evening of the sixth day they would travel for three hours by bus to the village from which they all came, outside Lahore. After a month of drawing in their workshop, they invited me to come to meet their children, wives, and parents. In the village they handed over the money for which they had worked their hands to the bone, ate a huge meal, and dandled their children on their laps. I drew their children and their wives and sat drinking chai as they played cards til well after midnight. We rose at 4 am the next morning for their prayer, before returning to the city to begin work, for it was Monday .